Conflict Resolution through Mapping

Puerto Rico Today

Debt and Disaster Following the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in September 2017, Puerto Rico’s electrical grid failed, water systems were inoperable, debris from landslides blocked roads, cellular sites were knocked out, and households were damaged, among the numerous other challenges.[1] This natural disaster put Puerto Rico in the spotlight for relief, but the U.S. Territory had already been struggling with a financial crisis as a consequence of its colonial history and limited sovereignty. Home to 3.5 million residents and homeland to 5 million in the diaspora, Puerto Rico surpassed a point of bankruptcy in 2015, accumulating $72 billion in debt, more than its Gross National product (GNP).[2] The outstanding debt burden had already burdened Puerto Rico from providing adequate services to its people, with the closure of over 150 schools, increased taxes, laying off public workers, shortage of medical specialists, and increasing emigration, unemployment, and food insecurity.[3] Although FEMA plans to provide $2.36 billion dollars in assistance to survivors on the island,[4] much of this relief aid is focused on restoring Puerto Rico to the already vulnerable state it was in prior to the hurricane. The aid of post-hurricane recovery resources presents an optimistic opportunity to invest in the future of Puerto Rico.

Taking the Matter into Their Own Hands As disaster funds for Puerto Rico are allocated, how and where funds are distributed reflect the political priorities of those in power. Through its history of colonization, the government authority has been widely distrusted by Puerto Rican communities to distribute funding appropriately. In March 2019, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development announced that they are auditing the funds that were granted to Puerto Rico for hurricane recovery,[5] and a local resident noted that “getting access to information here has always been a struggle.”[6] With the island’s deep history of resistance to colonization and paranoia of the government, Puerto Ricans have developed a great capacity to locally organize and advocate for their own needs.[7] If Puerto Ricans can provide a rational argument that spatializes the needs and priorities of their communities and speaks the language of planners, they can proactively advocate for where relief funds should be allocated. We propose the decision model to be used as a tool for communities to gain agency in mapping their priorities for improvements.

A Tool for Advocacy

What are Decision Models? In typical planning methodologies, decision models or Multicriteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) are “tools to augment, enable, or automate the decision-making process… where decision making is complex and/or requires several forms of input information.”[8] In a situation like Puerto Rico, with serious infrastructural damage to infrastructure from Hurricane Maria and many services cut due to austerity, a variety of factors will contribute to a decision making process on where to allocate recovery funds.

When place-based decisions are the focus of the analysis, a decision model can illustrate spatial relationships between multiple layers of information can be weighted, and can help us envision a strategy for prioritizing improvements for the future of Puerto Rico. Because decision models rely on a rational mathematic process, it is assumed that “good data may be all we need for objectivity and objectivity may be all we need for fairness.”[9]

However, this poses the question: The best decisions for whom?

Despite the logical method, data is biased and weighted priorities can favor different outcomes. Decision models should not be understood as objective stand-alone tools, but as a system to weigh the priorities of stakeholders. The potential to represent different values can assist collaborative negotiation and consensus building processes, “where multiple communities with differing priorities must negotiate political (planning) processes for public decision making, data-driven decision support tools have been used to help visualize and describe alternative scenarios and outcomes.”[9]

If we can teach community leaders how to read into the assumptions of maps created through MCDA and use the tool to promote their own values, we can equip them with the knowledge and tools to defend their own priorities. Our goal is to empower communities to use the decision model as a participatory tool for advocacy and negotiation.

Decision Mapping for Puerto Ricans This project is an empowering data and mapping literacy initiative to offer a new tool to a community that is ready to use it to push for their own needs with two main objectives. Firstly, decision based maps can be used to document community values by spatially recording information about Puerto Rican priorities in a map to imagine a future for the island. Secondly, these maps can be used as an advocacy tool for local leaders to communicate the needs of their communities within the language of planning ‘experts’ to rationally stake a claim for areas that should be prioritized for improvements.

Balancing Values

We pose the decision model methodology with the following objectives:

- All Puerto Ricans have the right to live in a community with access to adequate resources and basic services.

- All communities should be restored and resilient to future disaster risks.

- Recovery investment should be allocated to provide resources to strengthen the economy.

Conflicting Interests

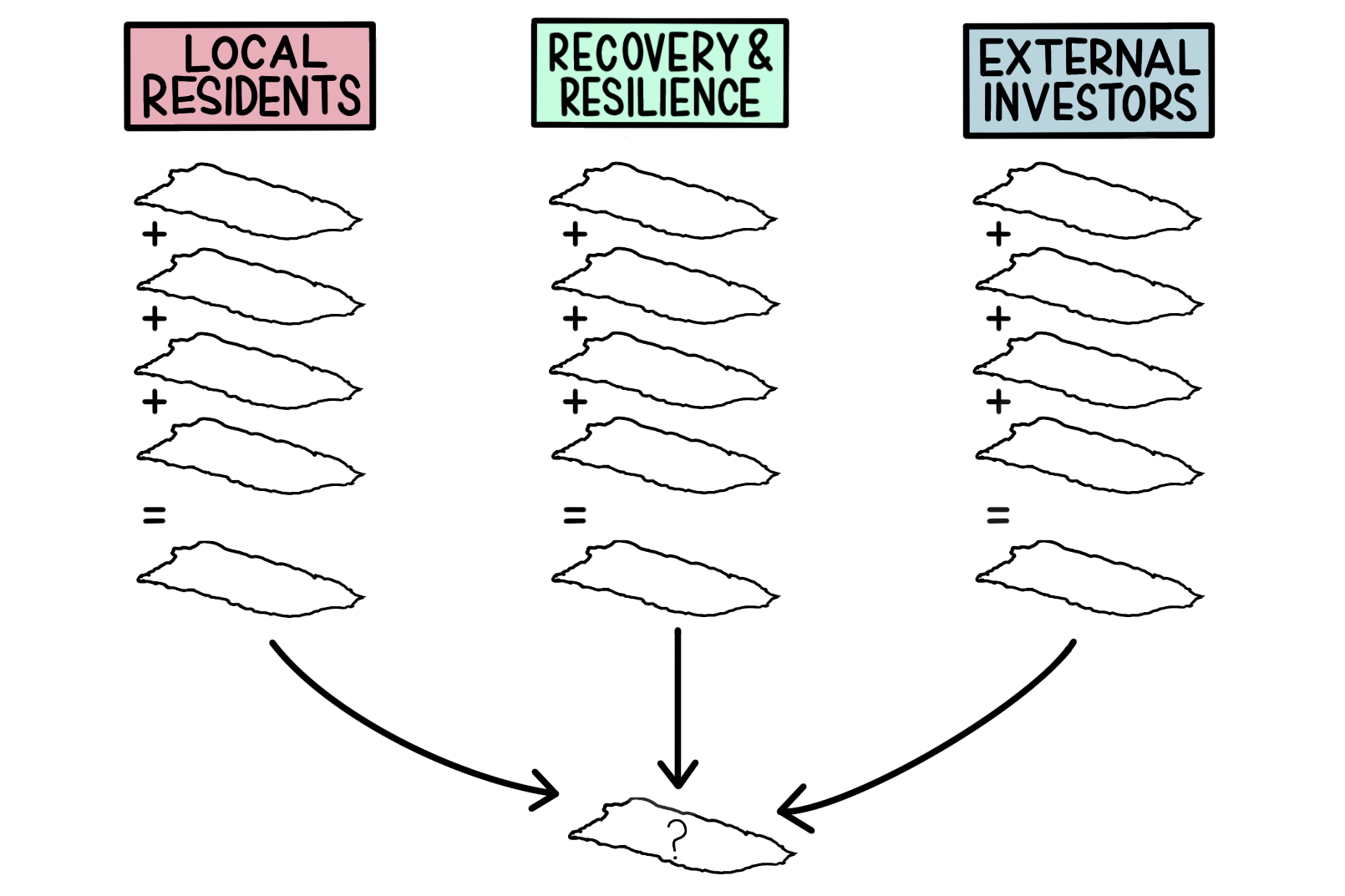

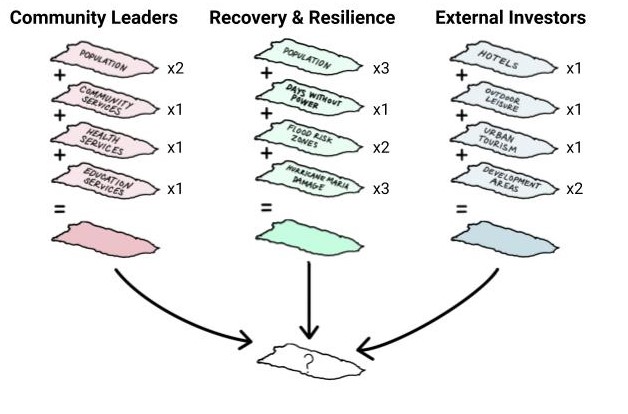

In order to demonstrate potentially conflicting stakeholder values, which can conclude in different visions for the future of Puerto Rico, we’ve created three fictional characters based on the narratives of perspectives and experiences that Puerto Ricans can relate to. Although fictional and exaggerated, the characterization of stakeholders is useful to illustrate how differences in priorities affect the final decision output.

Local Residents

Representative Group: local community leaders; Puerto Rican residents

It is common for the average Puerto Rican to put their family first, and often times these families are led by a female householder. Women are involved in heading almost 80% of households in Puerto Rico,[10] as well as being active leaders within their communities. With female-led family values extending into nurturing their neighborhoods, these local community activists may place greater priorities on equitably providing access to resources.

Prior to Hurricane Maria, the Puerto Rican government had already been struggling with an overwhelming amount of debt, and had already begun reducing its expenses by cutting back on public services. Because Puerto Rico has a high poverty rate, with an estimated 59% of households generated an income of less than $25,000 in 2017,[11] many of these services are a necessity for an adequate quality of life. After Hurricane Maria struck, Puerto Rican communities have seen the closure of many public schools and continue to receive inadequate funding for services as the government continues to deal with the debt crisis.

Priorities: long-term well-being of the community

- Provide equitable resources for underserved communities

- Long-term community resilience

- Access to infrastructure services

- Build robust economy

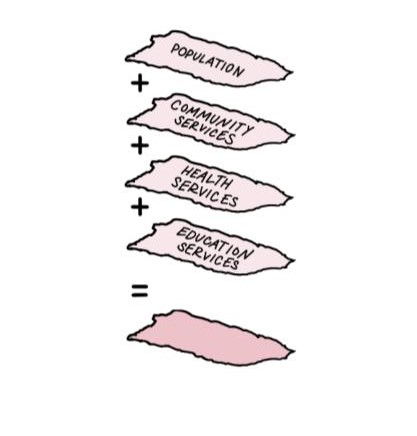

Data Layers Mapped:

- Population density

- Community services

- Health services

- Education services

Testimonials:

- “This is a moment of opportunity, even if we are the most hurt by the hurricane we can use this to change long term issues that have been affecting Puerto Rico before this”

- “We want to ensure access to underserved priorities”

- “Our concerns are longer term than the hurricane, we want to address the debt crisis and how it has affected the public services for the community”

- “Tania Ginés was fighting for 10 months to avoid the closure of her daughter’s public school. In the end, she lost the battle. Now, the children need to go to a further school, where there are more than 40 students per class, rats in the cafeteria, no therapists for special education children” ”

- Tania: “It is like I say, I mean, I didn’t borrow, my children did not borrow!”[12]

Local Residents Decision Model

To the active leaders in local Puerto Rican communities, recovery funding for Hurricane Maria presents an opportunity to invest in services to strengthen the social resilience network that was already lacking prior to Hurricane Maria. The priorities of local residents are visualized by considering the density of community populations are considered relative to areas with longer distances to reach community, health, and education services.

Data Sources

- US Census Bureau. "Annual Population Estimates for Puerto Rico and its municipalities," [vector]. April 2018.

- Humanitarian Data Exchange via OpenStreetMap. "HOTOSM Puerto Rico Buildings," [vector]. Nov 2018.

- Humanitarian Data Exchange via OpenStreetMap. "HOTOSM Puerto Rico Points of Interest," [vector]. Nov 2018.

Recovery & Resilience

Representative Group: Puerto Rican middle class; mainland emigrants who retain close ties to the island; disaster relief aides

After Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico, many residents were faced with repairing damaged homes and blocked roads and had limited access to basic services like electricity, potable water, and cellular service. The serverity of this natural disaster evoked a sense of urgency for local Puerto Ricans, emigrated Puerto Ricans, and the witnessing nation to send support for recovery through donations, volunteers, and FEMA disaster relief.

Within the greater context of climate change, natural disasters have become more intense and frequent within the last 15 years. Hurricane Maria’s destruction revealed that Puerto Rico’s power grid, water supply, and communities are highly vulnerable and lacked the ability to recovery quickly from the disaster.

Priorities: recovery and resilience

- Ensure the resilience of developed areas

- Recover from Hurricane Maria damage

- Reduce risk from future threats (i.e. hurricanes, flood inundation, landslides, etc.)

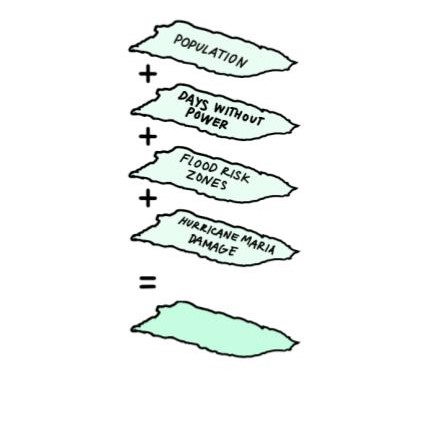

Data Layers Mapped:

- Population density

- Days without power

- Flood risk zones

- Hurricane Maria damage

Testimonials:

- “This was a terrible catastrophe for the island, we want to ensure that a disaster like that never happens again”

- “We want to participate in rebuilding the island after the hurricane”

- “It was the 70’s. Teresa was a young mother with two children an a house in the suburbs. She was a pharmaceutical chemist. The family had two sources of income: hers and her husband’s. They were the typical Puerto Rican middle class family”[13]

Recovery & Resilience Decision Model

Many people involved in Hurricane Maria disaster recovery efforts may prioritize imagining a more resilient Puerto Rico. Resiliency focuses on reducing vulnerability of city-wide systems and reinforcing social connections and resources within a network. To address recovery and resilience interests in Puerto Rico, areas with longer days without power, vulnerable to future flooding, and affected by Hurricane Maria are assessed relative to the population density of communities affected.

Data Sources

- US Census Bureau. "Annual Population Estimates for Puerto Rico and its municipalities," [vector]. April 2018.

- Humanitarian Data Exchange via OpenStreetMap. "HOTOSM Puerto Rico Buildings," [vector]. Nov 2018.

- NASA. "Days Without Power," [raster]. 2018.

- FEMA, Puerto Rico Planning Board. "HECRAS Modesl for the PR Advisory Maps," [vector]. Feb 2018.

- FEMA. "National Disasters: Hurricane Maria Damage Assessments," [vector]. Oct 2017. 2017

External Investors

Representative Group: real estate speculators, financial investors, and the top 1% of Puerto Ricans that support development

In the event of a disaster, like Hurricane Maria, there’s a lot of optimism that Puerto Rico will rebuild its islands to be better than its pre-disaster condition. Many external investors see Puerto Rico’s recovery as an opportunity to rebuild its infrastructure and a potential for future growth. With Puerto Rico as a U.S. territory, American citizens can travel to and from Puerto Rico without a visa or passport. Additionally, Puerto Rican legislation from 2012 includes a number of tax loopholes, which entice prospective businesses and investors with significantly lower tax rates that only requires residency for 183 days per year.[14]

With the lure of being an easily accessible island destination to U.S. citizens and the attraction of its tropical temperature and beautiful beaches, Puerto Rico is a desirable location for investors to play a role in the recovery process of the island, while gaining profit for themselves.

Priorities: attract capital to develop areas of the island for profit; invest in Puerto Rico as a tourist destination

- Improve areas with high economic growth potential

- Provide resources to resort and leisure developments

- Beautify tourist destination areas

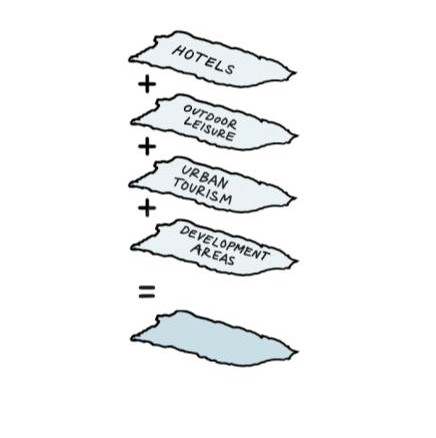

Data Layers Mapped:

- Hotels

- Outdoor leisure

- Urban and historic tourist destinations

- Development areas

External Investors Decision Model

Many external investors see Puerto Rico is a desirable location for investors to play a role in the recovery process of the island, while gaining profit for themselves. If tourist development were prioritized in Puerto Rico, areas with opportunity for development that are near existing hotels, outdoor leisure, and urban and historic destinations would be considered.

Data Sources

- Google Maps. "Hotels in Puerto Rico," [vector]. Accessed Apr 2019.

- Discover Puerto Rico. "Activities and Experiences: Beaches & Water Sports, Casinos, Culture, Golf, Luxury, Museums, Nightlife, Outdoors, Shopping," [vector] Accessed Apr 2019.

- Planning Board, Office of the Governor, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. "Map of land classification under the Land Use Plan" [vector] Dec 2015, updated Oct 2017.

Weighting Stakeholder Values

All the maps show a range of shades, from lighter to darker. Darker shades mean higher values, which also mean that those areas should be prioritized when deciding how to allocate resources in puerto Rico.

In Valeria’s map, we can see how the distribution is very spread out throughout the island, which indicates that all the Island is in need of more resources. In the case of Maria’s map, we can detect higher values on the North East coast of the Island. In this case, this area is prioritized because it was the most damaged by the hurricane, according to FEMA data, while also having higher density of population potentially affected by it. In the case of Bill, we can see how his map highly prioritizes coastal areas and urban centres. This is a result of being tourist locations and also areas with more potential for development. This map also shows a more unequal distribution, with the mentioned concentrated areas valued very high and the rest of the island valued very low.

If Valeria, Maria and Bill were on a meeting with all of them advocating for their own priorities, different results could be met. In the case of the three of them having the same type of agency and agreeing to balance their values, coastal and urban areas would still be prioritized, specially places like San Juan or El Ponce. However, certain central municipalities would still be given high values, such as the northern area of Utuado, Ciales or south of Coamo. In general, the maps also show how the municipality division are not a good spatial unit to distribute the resources, as their boundaries hardly match the different shades of prioritization.

If Maria and Valeria, the two puerto ricans, would align and impose their values, they would be able to press for more attention in the central areas of the Island, especially on the East side, arguing that they were more damaged by the hurricane and need more recovery funds. In addition, they could also argue for more access to services for the population, in municipalities like Villalba and Jayuya.

On the other side, if Maria decided to partner with Bill in order to focus on building a more competitive economy on the Island, rural areas would be more neglected, with the resources allocated in the coastal regions and the urban centers of population. San Juan, Ponce and Mumacao would receive the higher investment in that case.

Weighted Decision Model

Potential for Conflict Resolution

What is the impact? Breaking down the mapped decision model allows us to relate to the values of each character in the fictional advocacy scenario in order to collectively visualize the possible futures of Puerto Rico.

–

References

- “Hurricane Maria.” FEMA, U.S. Department of Homeland Security. March 14, 2019. <https://www.fema.gov/hurricane-maria>.

- Bannan, Natasha L. Puerto Rico’s Odious Debt: The Economic Crisis of Colonialism, 19 CUNY L. Rev. 287 (2016). <https://academicworks.cuny.edu/clr/vol19/iss2/5/>.

- Bannan, Natasha L.

- “Hurricane Maria.”

- Wiscovitch, Jeniffer. “HUD’s Inspector General is Auditing Part of the Disaster Funds for Puerto Rico.” Centro de Periodismo Investigativo. March 28, 2019. <http://periodismoinvestigativo.com/2019/03/huds-inspector-general-is-auditing-part-of-the-disaster-funds-for-puerto-rico/>.

- Florido, Adrian. “Puerto Ricans Want Their Government To Be More Transparent.” National Public Radio, Inc. November 19, 2018. <https://www.npr.org/2018/11/19/669145225/post-maria-puerto-ricans-want-their-government-to-be-more-transparent>.

- Laughland, Oliver. “‘I’m not fatalistic’: Naomi Klein on Puerto Rico, austerity and the left.” The Guardian. Aug 8, 2018. <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/08/naomi-klein-interview-puerto-rico-the-battle-for-paradise>.

- Meisterlin, Leah. "Multicriteria Decision Analysis." Geographic Information Systems, PLANA4577, Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. Lecture 2017.

- Meisterlin, Leah and Claire Newman. “New New Orleans vN.x: An Attempt at Rational Planning.” The Question of New Orleans. L Hawkinson, et al, Eds. Columbia University GSAPP. New York: The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York, 2006. 22-23.

- United States Census Bureau. "ACS 2017 (5-Year Estimates)," Social Explorer. Sep 2016. <https://www.socialexplorer.com/>

- United States Census Bureau. "ACS 2017 (5-Year Estimates)," Social Explorer. Sep 2016. <https://www.socialexplorer.com/>

- Transcripción: Deuda. Postcast: Radio Ambulante. Luis Trelles. 2016 http://radioambulante.org/transcripcion/transcripcion-deuda

- Transcripción: Deuda. Postcast: Radio Ambulante. Luis Trelles. 2016 http://radioambulante.org/transcripcion/transcripcion-deuda

- "Why now is the perfect time to invest in Puerto Rico." lifeafar Investments. 2019 <https://www.lifeafarinvestments.com/now-perfect-time-invest-puerto-rico/>